Stuck In Place

Yoni Appelbaum’s “Stuck In Place” accurately describes how restrictive land-use policies in America’s most economically vibrant cities have choked off opportunity for many Americans.

That said, I’m skeptical that homeowners would be as open to new development as Appelbaum thinks. One person’s exorbitant expense—money paid for rent or to purchase a home—is another person’s income. Increasing the housing supply to deliberately moderate or even lower prices threatens homeowners whose retirement plans include cashing in on the equity stake in their home.

Twenty-five years ago, William Fischel named this political economy the “homevoter hypothesis”: Voters lobby the local land-use authorities to protect their vested real-estate interests, thereby excluding newcomers from their communities.

Americans have grown accustomed to rapidly rising home values, and our federal, state, and local governments encourage this through zoning, mortgage, and tax policies. It’s no wonder people eagerly use the power of the state to privilege themselves, even if they couch it in lofty terms such as opposing “greedy developers” and “protecting neighborhood character.”

Eric Fidler

Washington, D.C.

Yoni Appelbaum’s article on the ills caused by progressives’ neighborhood preservationism is thought-provoking, well researched, and convincing to a point. But it can’t serve as a blanket explanation for all of America’s current sociopolitical ills—nothing fits that bill.

Arguments like these can lead to scapegoating and a backlash that itself goes too far. Zoning laws should certainly be loosened—but do we want to open every last historical landmark to the wrecking ball and allow every last green space in America to be paved over just so someone can make a quick buck? Surely we can strike a new, better balance.

Martin J. Berman-Gorvine

Potomac, Md.

I read Yoni Appelbaum’s lament over decreasing American mobility with bemusement. Some people value establishing and maintaining deep bonds with family, friends, and community over chasing after money. Here in rural northeastern Kansas, I dwell among people who live on the same land that their forebears homesteaded in the mid-19th century. They possess a sense of rootedness and purpose as vital contributors to their local community that cannot be exchanged for cash. They also tend to be thrifty people who save, so other than them tipping off friends about the latest sale at the fabric store, I’ve never heard them mention or complain about money.

Because of the quest for upward mobility, I know many couples whose grown children choose to pursue lives in California or Florida or New York and then cram into airports during the holidays. They would have saved themselves considerable time, money, and stress if they’d never left home in the first place. FaceTime and texting cannot babysit for you, mow your lawn, rescue you if your car breaks down, or run errands for you if you are sick. Mindlessly moving from one place to another in pursuit of the next promotion is not only extremely expensive—it has contributed to the loneliness epidemic. Neighbors no longer know one another; newcomers find themselves surrounded by strangers. And if they are transients who will jump at the next opportunity to relocate, I doubt that they will try to establish any meaningful connections.

The pursuit of more money through mobility is a dominant theme in our culture, but not everyone buys into it. I’ve discovered meaning and fulfillment by staying in one place.

Margaret Kramar

Lecompton, Kan.

Here’s another reason fewer Americans are moving far from their hometowns: the increased economic and social power of women. Women do a disproportionate amount of unpaid work in the form of child care and elder care. Women know how difficult it is to raise kids far away from the support of extended family. For the men who were the breadwinners and decision makers of previous generations, caring for children (to say nothing of aging parents) was not their concern. To modern couples who earn money and make decisions more equitably, the demands of child care and elder care are powerful incentives to stay close to home.

Emily Murbarger

Philadelphia, Pa.

Yoni Appelbaum’s theory that progressives are to blame for America’s housing crisis ignores a far more obvious culprit: greed. The reason no one is building affordable housing is that it simply isn’t as profitable as luxury townhouses and condos. Downtown Milwaukee, for instance, teems with new apartment complexes marketed to those who can afford the $2,000 rent. There needs to be an incentive to build housing for the people who clean and service these units, especially as wealthy Americans turn their backs on the public sphere. Otherwise, our cities risk becoming hives of affluence.

David Southward

Milwaukee, Wis.

I wholeheartedly agree with Yoni Appelbaum’s three principles for restoring dynamism and mobility to our cities. We need more consistency and less discretion in our land-use rules. We need more tolerance for the messy process of change to the built environment. And we need to embrace growth and abundance.

But the correctness of Appelbaum’s conclusions only deepened my frustration with the blame he placed on Jane Jacobs. Although she deserves criticism for inspiring a strain of progressive NIMBYism, Jacobs was no evangelist for freezing cities in amber. She famously attacked “separation of uses”—then a key facet of planning orthodoxy—in her book The Death and Life of Great American Cities. She advocated instead for mixed-use streets where people and businesses would age in and out over time in a constant process of urban self-regeneration. That’s exactly the dynamism that Appelbaum wants.

True, Jacobs’s prescription was not as accurate as her diagnosis. It seems strange that she thought historic-preservation laws could be “zoning for diversity” rather than zoning for gentrification. But in the ’50s and ’60s, the government invested enormously in suburbanization, often by leveling neighborhoods to build highways. Americans should be a mobile people because we choose to be, not because Uncle Sam gives us an eviction notice. Jacobs’s fight is more understandable in that context. The problem isn’t what she did then; it’s that some self-described progressives still insist on her approach 70 years later in radically changed circumstances. Fortunately, they are drowned out more and more by a new progressive movement that proclaims, “Yes in my backyard.”

Michael Whelan

Ann Arbor, Mich.

There are times when moving house makes sense—say, a job change, or a significant change in the size of one’s family. But there is also much to be said for simply being satisfied with what one has. I do realize that it is not a typically American attitude, but it is an attitude that can bring about a fair degree of happiness. Perpetual striving leads only to more striving.

Allen Murray

Mebane, N.C.

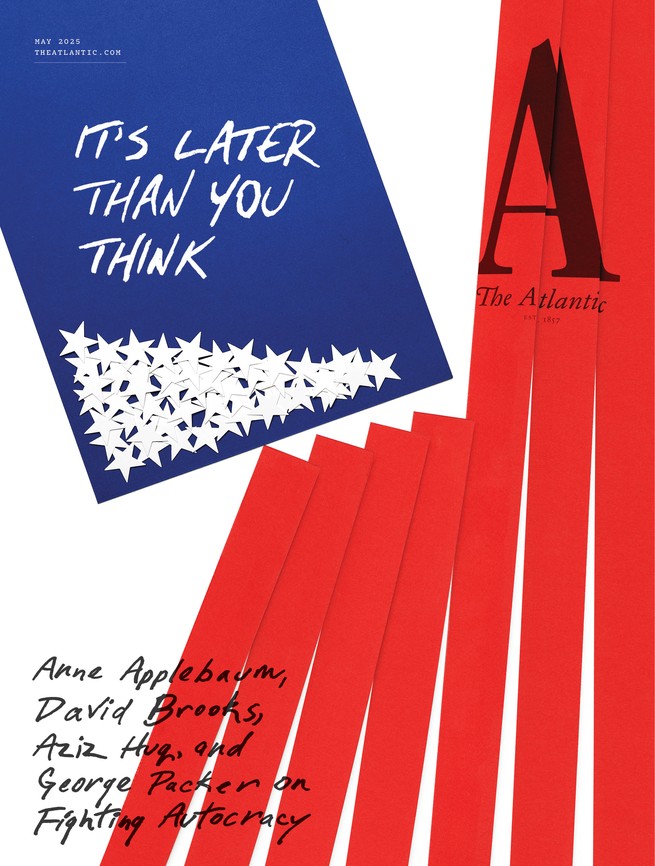

Behind the Cover

This month, our cover spotlights four stories on threats to American democracy. George Packer examines President Donald Trump’s Orwellian tendencies. Anne Applebaum reports on the right’s dangerous embrace of Viktor Orbán’s Hungary. Aziz Huq recounts how the constitutional and legal foundations of the Weimar Republic eroded. And David Brooks describes the nihilism at the core of the MAGA movement. For the cover image, the illustrator Ricardo Tomás created an imperiled American flag, its stars and stripes on the verge of collapse.

— Paul Spella, Senior Art Director

Correction

A caption in “O’Keeffe in the Frame” (February) misstated the location of Twilight Canyon. It is in Utah, not New Mexico.

This article appears in the May 2025 print edition with the headline “The Commons.”