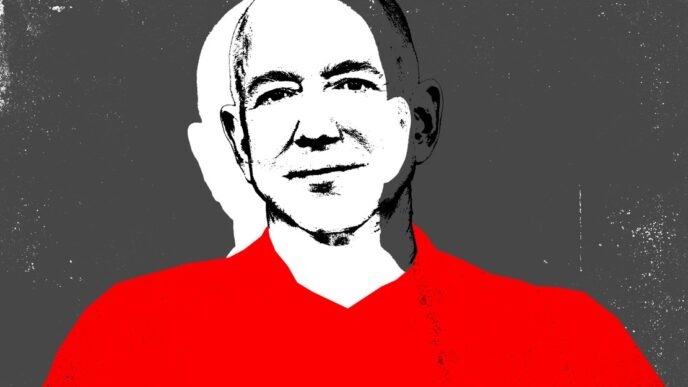

When tech billionaires and crypto moguls hailed Donald Trump’s reelection and flocked to his inauguration ceremony and ball, million-dollar donations in hand, some were abandoning previous liberal affiliations and all were now lining up behind an openly authoritarian president. The surface rationale is that megabusiness leaders such as Mark Zuckerberg, Jeff Bezos, Tim Cook, and Marc Andreessen are safeguarding their companies and their shareholders’ interests. The underlying explanation is that America is being reborn as an oligarchy.

This new class—with Trump megadonor Elon Musk as its self-appointed tribune—has thrown its support behind a libertarian economic agenda that maximizes private power and minimizes public accountability. Whether the billionaires’ alignment with Trump and Musk is merely pragmatic or sincerely ideological, they stand to gain from the new administration’s crash program of dismantling government and regulatory agencies. For Trump, allying with such concentrated economic power helps him consolidate political control, at the expense of democracy. This fusion of money and power is nothing new. I saw something similar take shape in my native Russia. But three decades later, the Russian oligarchs’ bargain has ended up with only one true beneficiary: Vladimir Putin.

America’s billionaires should take note. When extreme wealth combines forces with extreme power, the former can profit enormously for a time. As in Russia, the benefits of the executive’s policies are likely to flow upward: Super-wealthy Americans will enjoy tax breaks and deregulation for their businesses, while the poor will face rising prices, shrinking services, and reduced opportunity. But America’s tech oligarchs may discover sooner rather than later that, by undermining democratic governance, they are empowering an authoritarian president who can pick them off one by one—just as Putin did with the oligarchs who helped cement his rule.

When Communism collapsed in 1991 and Russia pivoted to capitalism, the country’s wealth quickly ended up in the hands of a few newly minted businessmen. A mix of small-time entrepreneurs, opportunistic academics, mid-level functionaries, and shady characters with ties to organized crime, these men affiliated themselves with Boris Yeltsin’s post-Soviet government. By arranging loans for Yeltsin’s floundering administration in return for stakes in privatized industries, they profited directly from the fire sale of state assets.

Among the most prominent of these oligarchs, as they became known, were Boris Berezovsky, a mathematician turned media mogul; Mikhail Khodorkovsky, a former Komsomol activist who became the owner of the oil-and-gas giant Yukos; and Vladimir Gusinsky, a theater-academy graduate who leveraged his ties to Moscow’s elite to build a banking, real-estate, and media empire. While these businessmen rode around in bulletproof limousines and dropped $10,000 a bottle on champagne at ritzy new nightclubs, the rest of the country—already reeling from the Washington Consensus–inspired shock therapy that dismantled price controls, triggering hyperinflation—watched their savings vanish and sank deeper into poverty.

By the 1996 election, resentment of the Yeltsin circle’s insider deals was so great that the Communist Party, in disgrace five years earlier, staged a comeback that saw its candidate compete in a runoff with Yeltsin. Into this chaotic scene came Putin, a former KGB officer who joined the Yeltsin administration that year and became its security chief in 1998. In 1999, Putin was appointed prime minister; in 2000, after Yeltsin’s resignation, he was elected president.

The oligarchs had sponsored his rise as a dependable apparatchik who would instill order and protect their state-asset acquisitions. They misjudged him: Barely a month after his inauguration, Putin reversed the master-servant hierarchy. In June, Gusinsky was arrested on corruption charges and pressured into relinquishing control of his media holdings to the state-owned Gazprom in exchange for his release. Soon after, Berezovsky fled the country when confronted with similar tactics. Both men were accused of fraud and embezzlement. Russia’s top law-enforcement officer, the prosecutor general, is—like the attorney general in the United States—a presidential nominee. These prosecutions were widely seen as politically motivated.

Putin had sent a message: The oligarchs could keep their wealth as long as they obeyed his dictates and stayed out of politics. These moves met no resistance in the courts or from the Duma, Russia’s parliament. Instead, lawmakers immediately granted the president additional powers that enabled him to weaken Russian federalism—dismantling the autonomy that local elites had enjoyed under Yeltsin—and to centralize power in the Kremlin.

Superficially, Putin’s action looked like a renationalization of state assets. In practice, it was a wealth transfer to loyalists and security-service allies. This process culminated in the 2003 takeover of Yukos. Khodorkovsky, then the richest man in Russia and a notable backer of Western-style liberal democracy, was jailed. Yukos’s assets were first frozen and then sold off at auction. The main chunk went to the state-controlled Rosneft corporation, which was led by another former KGB officer, the Putin confidant Igor Sechin. Khodorkovsky’s lawyers faced retaliation for representing their client against the government prosecution.

With that, Putin had ended Russia’s brief experiment in liberalization. Now he set about reshaping the political architecture of post-Soviet Russia.

The horrific 2004 Beslan hostage crisis, when a school siege by Chechen separatists ended in a botched rescue by Russian forces and hundreds of civilian deaths, gave him his opportunity. Under the pretext of fighting terrorism, Putin abolished direct elections for provincial governors and installed Kremlin appointees. He used administrative means to suppress political opponents: Candidates seeking office faced burdensome signature requirements, registration denials, or disqualification on technicalities. Serious challengers such as Alexei Navalny faced trumped-up charges of embezzlement and fraud.

Putin also moved to crush Russia’s free press by revoking licenses for independent media, forcing ownership changes, and installing editorial teams that would stick to Kremlin-approved narratives. With a series of laws, Putin escalated measures against foreign NGOs, criminalizing their activity and cutting funding for human-rights work in Russia.

In a charade of compliance with presidential term limits, Putin stood down in 2008, serving as prime minister under his protégé, President Dmitry Medvedev. Exploiting a constitutional loophole that barred only consecutive terms, Putin returned to the presidency in 2012—and then secured an amendment in 2020 that reset his term count and will allow him to remain in office until 2036. After public demonstrations against election fraud in 2011 and 2012, his government imposed harsh penalties for “unauthorized protests”; today, even a single person with a placard violates the law.

The Russian Orthodox Church has been a major sponsor of Putin’s regime. The Church’s head since 2009 has been Patriarch Kirill, an ultra-wealthy oligarch in his own right, with a fortune estimated at $4 billion. Declaring Putin’s leadership “a miracle of God” in 2012, the patriarch has provided important ideological buttressing for Putin, reframing his neo-imperialist project as a metaphysical struggle against forces opposing the “Russian world” (a Völkisch concept encompassing any territory with a Russian-speaking population). Under Putin, Orthodox priests have become regular fixtures in schools, at official ceremonies such as rocket launches, and at the front in Ukraine.

Wrapped in the Russian flag and carrying an Orthodox cross, Putin has gone about making Russia great again—with the help of his obedient oligarchs. When Russia seized Crimea, in 2014, his closest allies took a cut of Ukrainian assets: Arkady Rotenberg, the president’s former judo partner, acquired confiscated land and was awarded a $3.6 billion contract to build the Crimea Bridge. By Putin’s fifth-term reelection last year, the business elite had little choice but to back his “special military operation” in Ukraine: The oligarchs’ collaboration successfully shielded them from U.S. and European sanctions, and the combined wealth of Russia’s 10 richest billionaires has grown since 2023. But there’s a catch: Even the oligarchs live in terror. Among the numerous Russian businessmen to have suffered a fatal fall from a window in recent years was Ravil Maganov, the chairman of Lukoil, after his company called for an end to the war in Ukraine.

Putin’s regime offers a stark illustration of how democratic institutions can be hollowed out. Some of Trump’s recent moves contain echoes of Kremlin strategy: canceling institutional checks in favor of loyalist appointments, attacking lawyers who work for opponents, demolishing independent agencies, feeding popular delusions of imperial greatness by threatening neighbors. The reforms of Musk’s DOGE outfit are set to shift public goods into private hands.

America is not Russia, and no billionaires are falling from windows here. The U.S. economy remains far more diverse and dynamic, and far larger, than Russia’s, but its competitive edge is already challenged by China, a threat that Trump’s tariff policy is unlikely to offset. America’s competitive advantages may start to erode under the new administration’s war on science and education. That already happened in Russia: Once a scientific and cultural powerhouse, the country is now a rigid petrostate. Over the past two decades, Russia’s scientific community has contracted by about 25 percent, thanks to declining educational standards and a brain drain of self-exiled talent.

An authoritarian oligarchy is not a pleasant place to live in. Ask my 88-year-old aunt, who was hit by a car in a provincial Russian town some years ago and can no longer leave her apartment because of the long-term injuries she sustained. After the case was investigated, she was pressured to withdraw her testimony because the driver was the son of a local official. That is how Putin’s “power vertical,” as Russian political parlance refers to his highly centralized, top-down authority, reaches into the lives of the little people. The oligarchy’s erosion of the rule of law trickles down, corroding public trust and ultimately leaving everyone—elites and ordinary citizens alike—at the mercy of arbitrary absolutism. The billionaire class now rallying behind Trump would do well to consider the implications of such a partnership.

For now, America still has a functioning electoral system, democratic institutions that have endured for centuries rather than decades, and a diverse, vibrant civil society. It also holds a vision of itself, enshrined in the Declaration of Independence, in which everyone has the right to pursue a fulfilling and self-determined life. But as Putin showed, constitutions can be amended or worked around; Trump is already musing about a third term. To follow Russia’s cynical path—whereby an all-powerful ruler feeds the masses false promises of greatness and keeps the oligarchs in line with favors and threats—would be to lose sight of that vision.