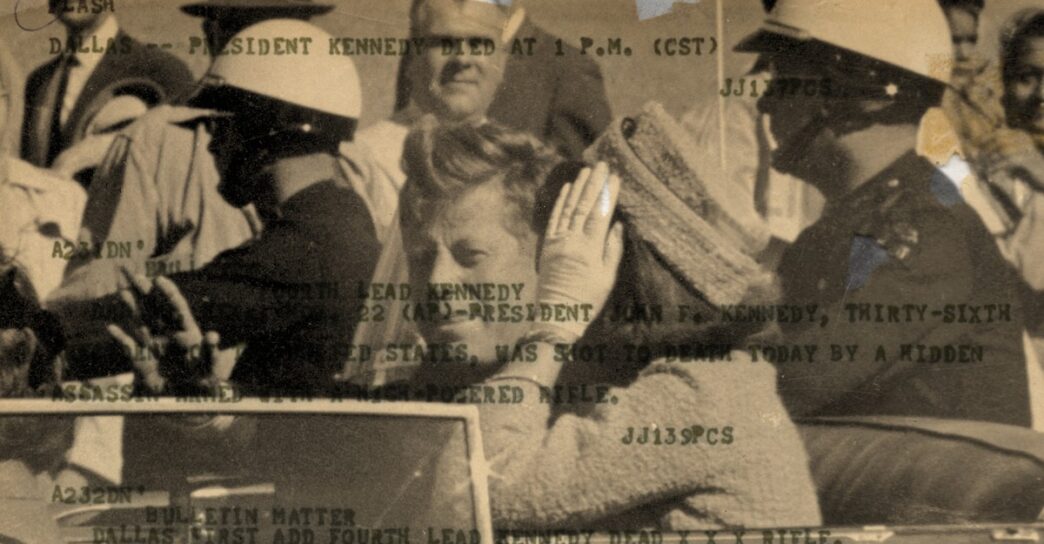

In 1962, the CIA had a driver’s license made for one of its officers, James P. O’Connell. It gave him an alias: James Paul Olds. We know this because the document containing the information was released to the public in 2017—part of an effort to declassify information related to John F. Kennedy’s assassination. But now, thanks to an executive order from President Donald Trump calling for the release of all the classified information pertaining to the incident, we know a bit more. It was, specifically, a California driver’s license.

This is an irrelevant detail in an irrelevant document. As far as anyone knows, O’Connell had nothing to do with the assassination; the inclusion of his story was probably just a by-product of an overly broad records request. But there it was on Tuesday evening, when the National Archives and Record Administration uploaded to its website about 63,400 pages of “JFK Assassination Records.” Given Trump’s order, the release of all this information sounded dramatic, but much of what has been revealed is about as interesting as that driver’s-license detail. Many of these documents were already public with minor redactions, and many of them have almost nothing to do with the Kennedy assassination and never did. This is why the Assassination Records Review Board, which processed them in the 1990s, labeled so many of them “Not Believed Relevant.”

Hundreds of thousands of such documents have been released since the ’90s, including thousands released during Trump’s first term and the Biden administration. (This is thanks to the President John F. Kennedy Assassination Records Collection Act of 1992, which was passed in response to overwhelming public interest in the case after the release of the Oliver Stone movie JFK.) But one of Trump’s 2024 campaign promises was to release all the rest; he said that it was “time for the American people to know the TRUTH!” His health secretary, Robert F. Kennedy Jr.—John Kennedy’s nephew—has been animated about the issue and framed the secrecy around the last files as evidence to support his conspiratorial view of history.

There are still some documents that the Archives could not make public, because they are subject to IRS privacy laws or because they come from sealed grand-jury proceedings. These may come out eventually, but they will likely follow the same drip, drip, drip as all the rest. It seems possible that the public’s curiosity will never be fully satisfied, at least in my lifetime. A new batch will always come out, but there will always be something left.

I’m one of the people who cares a lot about the Kennedy assassination. I’m currently finishing a book about the case. On principle, and out of selfish personal interest, I agree that the government should make all of the documents public if it can. Of course I scanned this new batch to see whether there was anything exciting. There wasn’t, but some of it was kind of funny.

In many cases, the removed redactions reveal proper nouns that a reader could have easily inferred before or that seem totally inconsequential. For instance, there is a 1974 memo about the Watergate conspirator E. Howard Hunt’s history with the CIA. A previously released version of the document mentions that the Office of Finance had asked a CIA station whether Hunt had received payments from it while he was living in Madrid. We did not know which station had been asked. Now we know it was the Madrid station. (Wow!) A 1977 document about the New York Times reporter Tad Szulc includes a rumor about Szulc being a Communist; in previous versions of the document, this information was “apparently from a [REDACTED] source.” With the redaction removed, we now know that it was “apparently from a British source.”

Some of it was less funny. The files also contain the unredacted personal information—including Social Security numbers—of dozens of people, seemingly published accidentally, though the National Archives site now suggests this was an inevitable result of the transparency effort. White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt acknowledged the problem to The New York Times on Thursday, saying, “At the request of the White House, the National Archives and the Social Security Administration immediately put together an action plan to proactively help individuals whose personal information was released in the files.” The National Archives did not respond to my request for comment.

In my scan, I came across the late-’70s personnel files of dozens of staff members of the House Select Committee on Assassinations, all of which contained Social Security numbers. A good number of those people are likely still alive. The document dump contains the Social Security number of a journalist who was active in the anti-war movement during the ’60s. There are, by my count, 19 documents about his personal life and employment history; none of the documents about him appears to have the faintest relevance to the assassination. Bizarrely, the new release also contains an unredacted arrest record for a Dealey Plaza witness who testified in front of the Warren Commission in 1964. This record—for the alleged theft of a car in 1970—has nothing whatsoever to do with the assassination of President Kennedy. Yet it is reproduced in full and it includes the man’s Social Security number and a full set of his fingerprints.

Relatively few of the documents even mention Kennedy. I saw only one addressed to him: a June 30, 1961, memo from his special assistant, confidant, and eventual biographer, Arthur Schlesinger about the growing power of the CIA. Most of it has been public since 2018, but the version released on Tuesday removed a final redaction about the agency’s extensive use of State Department jobs as cover for its agents. Schlesinger informed Kennedy that about 1,500 CIA agents abroad had State-provided cover stories at the time—too many, in his opinion; he wrote that “the effect is to further the CIA encroachment on the traditional functions of State.” The Paris embassy had 128 CIA people in it at the time, he added as an example. “CIA occupies the top floor of the Paris Embassy, a fact well known locally; and on the night of the Generals’ revolt in Algeria, passersby noted with amusement that the top floor was ablaze with lights.” Again, this is at best “kind of interesting” and at most trivia. It doesn’t meaningfully affect the historical understanding of President Kennedy’s tense relationship with the CIA, which is very well documented elsewhere.

After decades of releases, it may be that these are the only kinds of secrets the Archives still hold about the Kennedy assassination—tiny bits of color on things that are already well understood and boring details about people whose connections to the event are minimal if they even exist. But there’s no way to know until we see everything … if we see everything, if we ever can. Even then, when the count of secret things ticks down to zero, how will we know that was really, really all? We won’t, of course. We never will.