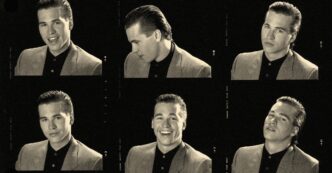

When Val Kilmer was a teenager, performing in high-school plays and making amateur movies with his younger brother, Marlon Brando was his hero. Like Brando, Kilmer eventually moved to New York to study acting, becoming one of the youngest students to be admitted to the Juilliard School’s drama program. And years later, after he acted alongside Brando in the infamously disastrous The Island of Dr. Moreau, Kilmer would nonetheless express a twisted kind of admiration for his co-star. “I wouldn’t call him normal,” he said of Brando on Late Show With David Letterman. “He’s a genius. Have you ever met any normal geniuses?”

Kilmer, who died last week at the age of 65, wasn’t “normal” either—which I mean as a high compliment. His commitment to the profession, the intensity of his working process, the curiosity and at times inscrutable logic guiding his choices of roles—all suggested that he knew no masters. Kilmer worked with auteurs such as Francis Ford Coppola and Michael Mann but turned down offers from David Lynch and Robert Altman. He was Moses and Batman and he starred in not one but two direct-to-video action movies with 50 Cent. As he explained in Val, the 2021 documentary about his life, he was driven by the desire to explore the mysterious space between “where you end and the character begins.” Although several obituaries have focused on his well-known roles, Kilmer didn’t need to be a leading man for his powers to shine through; his touch was so formidable that you felt it in transience too.

Because Kilmer was staggeringly handsome, and because he made headlines for his on-set clashes, he was often thought of as a mere movie star. Arguably, his two most iconic roles—as “Iceman” Kazansky in Top Gun and Jim Morrison in The Doors—echoed the rise of the brawny, big-budget blockbuster and of MTV, shaping his image along the contours of America’s pop-cultural trends. Yet celebrity’s glossy facades can obscure finer truths. He was also a consummate shape-shifter: a soulful brute in Heat, a twinkle-eyed gunslinger in Tombstone, a sardonic private eye in Kiss Kiss Bang Bang. Even in his tiniest roles, he made big impressions. It didn’t matter if the camera was elsewhere or if he wasn’t given any written lines.

Consider True Romance, the second of Kilmer’s three collaborations with the cult action director Tony Scott—which features one of his most nefarious characters, despite the brevity of the part. In this shoot-’em-up written by Quentin Tarantino, Clarence (played by Christian Slater), a nerdy comic-book-store employee, becomes an outlaw figure after he falls in love with Alabama, a sex worker played by Patricia Arquette. His transformation represents a fraught passage into manhood—Clarence feels emboldened to protect his lady’s honor, yet he dictates his life according to the violent fictional worlds of cartoons and movies.

Enter Kilmer, who plays a phantasmagorical version of Elvis Presley that’s the literal embodiment of Clarence’s conscience. He doesn’t have more than a few minutes of screen time, and you can’t even really make out his face, because the camera mostly captures him from neck down or in the distance as a fuzzy specter. But his arrival shifts the film’s entire mood, as his baritone murmurings cast a sort of hypnosis on Clarence. Like a Faustian figure, Kilmer’s Elvis plays to Clarence’s macho aspiration. He’s seductively cool, slinking in the background like a panther in one moment and then—bam!—pointing at Clarence with a sharp, extended finger, inciting him to man up. It’s a captivating performance that in a handful of hazy moments manages to anchor the film’s self-critique.

Kilmer, a lifelong Christian Scientist, claimed that he was too sensitive to dabble in drug use, even when his immersive preparation methods for movies such as The Doors and Wonderland (a thriller about the 1981 Wonderland murders in which Kilmer plays the adult-film star John Holmes) might’ve warranted some experimentation. His fiery public image and the ease with which he embodied strung-out party people made it easy to assume that his own lifestyle was similarly raucous. Yet Kilmer could do disturbed au naturel. Case in point: his indelible cameo as Duane, an aging rocker, in Terrence Malick’s Song to Song, in which he swoops into the drearily moody drama with the force of a mythological lightning bolt.

Midway through the film, as two of its several romantically entangled characters exchange charged glances at a Texas music festival, a snippet of voice-over narration wonders about the appeal of chaos: “Maybe what stirs your blood is having wild people around you,” one of the characters thinks about another. In response, Duane seems to materialize out of nowhere. As the ostensible front man of the garage-punk band the Black Lips, Kilmer’s character heeds this call of the wild in less than a minute, taking a chain saw to a speaker, cutting off chunks of his hair, and bellowing at the crowd while he holds up what he claims is a bucket of uranium. The actor’s frayed mane and lumbering gait tell us that Duane is as accustomed to the stage as he is to being dragged off of it. And when he’s actually pulled away and thrown into the back of a cab, Kilmer’s exit is as unceremonious as a cable yanked out from an amp, leaving viewers drifting along the film’s woozy currents.

Kilmer’s final performance would also take the form of a cameo. In Top Gun: Maverick, he reprises the role of Iceman in a small yet arresting scene opposite Maverick (Tom Cruise), his rival turned ally from the first movie. In the sequel, Maverick has come to his old comrade seeking advice. When Kilmer was diagnosed with throat cancer in 2014, the procedures he underwent severely damaged his vocal cords, altering the sound of his voice and limiting his ability to speak. To accommodate Kilmer’s disability, Iceman was written as struggling with cancer too; Kilmer appears with a scarf wrapped around his neck to conceal his surgical scars as he delivers a mostly wordless performance. When Iceman types out his thoughts on a computer, his silence is moving. From his earliest roles, Kilmer flaunted his singing abilities and an incredible talent for transforming his voice. Here, the memory of the characters he played fills the ensuing quiet.

Still, when the camera cuts to Kilmer’s face, he flashes the same cocky, knowing gaze of his youth, collapsing the distinction between where he ends and Iceman begins. He was an actor who could complicate the entire meaning of a film with a strut and a glimpse, and convey savagely weird and wonderful humanity in a brief encounter. Kilmer brought characters to life as extensions of himself. No gesture or look was too little.