Pity the documentary filmmaker: A job already replete with near impossibilities—impossible to secure funding, impossible to get distribution, impossible to find an attentive audience—has just become even more difficult. The Trump administration cut funding last week to nearly all of the National Endowment for the Humanities’ current grants—1,200 of them—including one to Yuriko Romer’s decade-in-the-making project. She was working on a film about baseball’s role in American-Japenese relations over the past 150 years. Donald Trump has decided instead that the NEH’s funds would be better spent on his own dream project: a sprawling sculpture garden with 250 likenesses of people he deems “American heroes.” Romer may one day look up at the stony faces of Daniel Boone or Betsy Ross in their patriotic splendor and decide that her sacrifice was worth it. But I doubt it.

Effectively killing the NEH in its current form and then reallocating its money to build the National Garden of American Heroes—the centerpiece of Trump’s plans to celebrate the 250th anniversary of the United States (thus, 250 sculptures)—is yet one more missile launched in his administration’s ongoing culture war. At stake in this case, however, is an enormous transfer of resources. More than Trump’s vague desire to stage Cats at the Kennedy Center, this act clarifies, in surprisingly concrete terms, the vision of American culture that the administration wants to bring to life—and the one it seems determined to destroy.

No ideological links connect the NEH grantees who lost their funding. The cut was so deep and wide—eliminating 85 percent of all existing grants—that the reasoning seemed to extend beyond the narrower task of demolishing “wokeness” that has so far been the administration’s animating cultural mission. The canceled NEH grants included a project to compile and translate Yiddish and Russian writing about the Holocaust from the Soviet Union, a two-week summer workshop for middle- and high-school teachers about the history and literature of the Chihuahuan Desert, and a feature-length documentary about stuttering.

This is an attack on intellectual and historical inquiry, no matter what one thinks of individual projects, even the silly-sounding ones. These endeavors, taken together, are about asking questions, about uncovering hidden or overlooked experiences, about closely examining texts or adding to the public record. The NEH helps fund the work of academics—but also artists and thinkers looking to creatively pursue the answers to societal dilemmas. The resulting work is not as obviously or immediately profitable as, say, scientific research—though funding for that is also being cut—but it does add to our collective knowledge, an ineffably valuable storeroom that needs constant replenishing.

Perhaps a valid argument could be made that the government simply shouldn’t be in the business of funding films and museum exhibitions. Or that more funding should go to projects that conservatives might find valuable—analyzing Christian texts, for example, or reviving classical education. But Trump is not interested in these finer points. He is sending a larger message about what he believes to be a better, more American, way to influence the culture through federal spending.

The budget of the NEH is about $210 million, $65 million of which goes to state humanities councils that need this money to survive. The current move will cut the agency from 170 to 50 staff members, and it’s unclear how many, if any, grants it will fulfill going forward. From this dwindling budget, $17 million will be repurposed for the garden (another $17 million will come from the National Endowment for the Arts, which also faces cuts). Will this $34 million be enough seed money for the National Garden? At the meeting last Wednesday during which these changes were announced, the interim head of the NEH also estimated that each of the 250 statues would cost $100,000 to $200,000, bringing the total cost as high as $50 million. And this may have been a lowball figure. The recent bronze statue of Billy Graham erected in the Capitol reportedly cost its private funders $650,000. Adding insult to injury, the acting head also said that the remaining NEH staff could still prove useful by making signs for the garden’s statues.

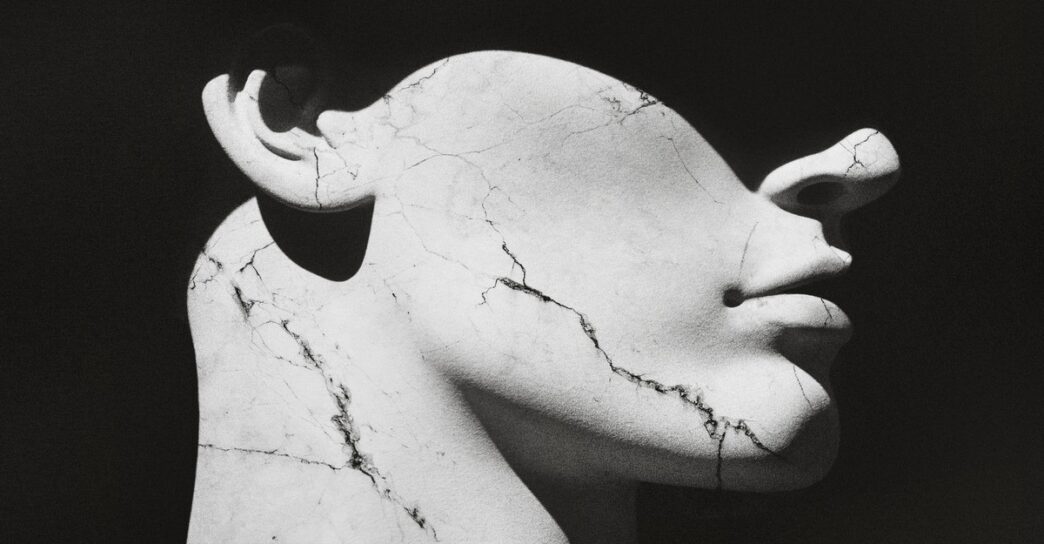

The repurposing of these funds represents not only a change in priorities but a fundamental shift of values for the federal government. Where the NEH has supported inquiry, the National Garden of American Heroes demands reverence. Trump’s idea for an “unbelievable” “beautiful outdoor statue park” sounds a bit like Disneyland’s animatronic Hall of Presidents. Less amusingly, it also sounds like the Foro Mussolini, the massive neoclassical complex that the fascist dictator built in Rome, which is lined with statues of idealized athletes and features a 50-foot obelisk inscribed Mussolini Dux. You cannot ask questions of a statue. You can only stare and contemplate and then move on. This is a manner of codifying history and closing the books. The way Trump has described it makes it sound like a mausoleum of sorts, an American Pantheon. In February, he even joked about including Tiger Woods (“I was going to put Tiger in the garden”), before realizing it should be reserved for dead heroes.

The mention of Woods came at a Black History Month celebration at the White House, where Trump talked up the garden and the fact that it would include Black historical figures such as Harriet Tubman and Booker T. Washington. But his recitation of Black Americans’ names also revealed that they were heavily weighted toward athletes and performers like Jackie Robinson and Aretha Franklin (on a list that includes relatively obscure conservative white thinkers such as Whittaker Chambers and Clare Boothe Luce).

This is sanded-down history, and in the zero-sum situation that Trump has created, the money it will cost will be money not spent on exploring history’s rougher edges. I looked to see if Shirley Chisholm, the firebrand politician who was the first Black woman elected to Congress, was in the list of potential statues. She was not (though Shirley Temple was). But in the process, I learned that among the canceled grants was a $100,000 disbursement to the Museum of the City of New York for an exhibit to look at Chisholm’s complex legacy on what would have been her 100th birthday.

When a culture moves from inquiry to reverence—with tens of millions of dollars facilitating the shift—it becomes propagandistic. Instead of fueling the passionate work of researchers and writers and curators, the same pot of money will be turned, literally, into stone.

Great civilizations have left behind statues—and coliseums and pyramids. They attest to a certain civilizational glory, the kind that has amassed enough riches to leave physical stamps on the world. But when I look into the marbled eyes of a Roman bust, I see what was frozen in time, what was once powerful and great, not what still is. There is beauty and artistic genius in these statues, but what they preserve is a desperate need to prove that power does not fade, that it can last forever if molded into the sturdiest material. In fact, power does fade—and so do its physical manifestations, victims to water, wind, and looters. What doesn’t fade, but only accrues, is knowledge. I will take the glory of the archive over the hubris of a statue every time. As a monument, the archive changes constantly; it argues with itself. It is forever expanding, permeable, and accessible, funded and created not by sculptors and their patrons but, potentially, by all of us.

There is something perverse about a civilization that plunders its archives to build statues. As Hannah Arendt, who by some strange cosmic joke is listed among the garden’s future heroes, might put it: Statues are a form of propaganda because they insist, in their inviolability, on ideological conformity, on the one right way to understand history and the present. There is no one right way, of course. But when it comes to influencing the culture, there are wrong choices, including the one Trump is making for all of us—one we are meant not to question but to revere.