Is the U.S. in a second Gilded Age? Many in the news media seem to think so: You’ll find the claim in The New Yorker, NPR, Politico, and these pages. The White House, for its part, seems to think that would be a good thing: “We were at our richest from 1870 to 1913,” Donald Trump said days into his second presidential term, a period that covers—that’s right—the Gilded Age. Although the claim was factually lacking, it was politically prophetic. Trump has governed like a late-19th-century president, with his penchant for tariffs, his unusual relationship with a major industrial titan, and his bald-faced corruption.

It’s widely understood that the late 19th century was an age of technological splendor and economic consolidation, and this is true enough. Thomas Scott and Cornelius Vanderbilt and Jay Gould dominated the railroads. John D. Rockefeller dominated oil. Andrew Carnegie dominated steel. J. P. Morgan dominated finance. We can see echoes here in the titans of modern industry: Jeff Bezos and the Waltons in commerce; Tim Cook and smartphones; Mark Zuckerberg and our attention; Elon Musk in space.

But some of the most interesting echoes of the Gilded Age involve the government’s relationship to business. In March, The Wall Street Journal reported that the Trump family held talks to pardon a major crypto executive who had pleaded guilty to money laundering. In exchange, they would secure a stake in his company, Binance. Similarly, in the late 19th century, which was an era of unusual grift, a range of public servants—from White House Cabinet members to local deputy sheriffs—were unembarrassed about skimming fees and taking bribes.

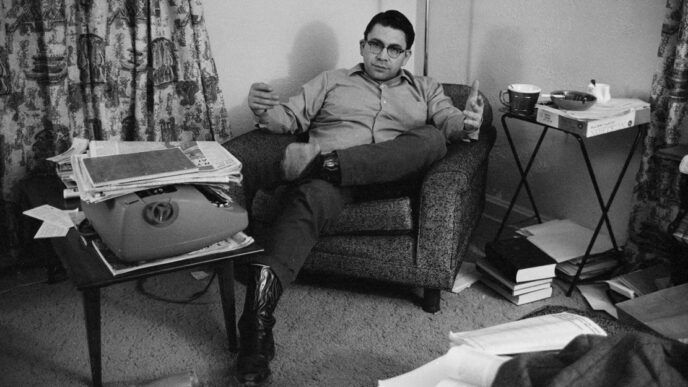

To understand what made the late 19th century gilded, I spoke with Richard White, the historian and author of The Republic for Which It Stands, a mammoth history of America between the end of the Civil War and the end of the 19th century. This conversation, which originally appeared on the podcast Plain English, has been truncated and edited.

Derek Thompson: The driving of the golden spike at Promontory Point in 1869 marked the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad. The Gilded Age begins just after and extends into the early 1900s. How did the transcontinental rail system set the stage for the Gilded Age?

Richard White: At the end of the Civil War, the United States was a country of vast ambitions and relatively little money. What it wanted to do was build an infrastructure to connect California to the rest of the United States. It didn’t have the money to do that, so it resorted to a series of subsidies and cooperation with private capital. The railroads were the great corporations of the United States at the core of the American economy. But the railroads depended on a system of insider dealing, corruption, and stock manipulation, in which people who accrued great wealth accrued great influence over the course of the United States. This system went on to define the Gilded Age.

Thompson: In the introduction of The Republic for Which It Stands, you write: “The Gilded Age was corrupt and corruption in government and business mattered. Corruption suffused government and the economy.” How?

White: People described each other as “friends.” They weren’t friendly in any colloquial sense that we understand. Friendship in the 19th-century sense was a relationship devoid of any affection in which people pursued common ends by scratching each other’s back. The railroad businessmen were friends with politicians, friends with newspapermen, friends with bankers. It was an age of dishonest cooperation.

Thompson: There are so many incredible characters from this period of American history: Rockefeller, Carnegie, J. P. Morgan. Who was John Rockefeller, and how did his style of cooperation typify this era of corrupt monopoly?

White: Rockefeller created what became the model corporation: Standard Oil. What he wanted to do was to organize a system he saw as too competitive and wildly inefficient. Rockefeller realized that there was just too much oil. He realized that if you were going to get profit, you had to eliminate the number of refineries. So Rockefeller went to the railroads and said, “I will give you all of my oil, but you have to kick back money to me—and don’t do it for my competitors.” Competitors soon found they couldn’t compete with Rockefeller, and so he came in and bought them out. By the 1890s, he was saying, “This is a new age, an age of cooperation.” And what he called cooperation, his opponents called monopoly.

Thompson: The U.S. government protected the monopolies in several ways. Steel tariffs helped Andrew Carnegie build his business, and in exchange Carnegie fed information to politicians. The government also quashed labor when it threatened big businesses in the late 19th century. Why does the state side with the monopolies again and again in this period?

White: Very often, the people in office were corrupt. The big industrialists would tell congressmen and senators: “When this is done, you’re going to serve a term or two, then come to work for us.” Or: “I’ll loan you a few thousand dollars to invest it in this.” Or: “I got a land grant from you, and in return, I’ll use part of the land grant to kick back to you under a fake trustee.” I mean, the industrialist Cosby Huntington wrote a letter to his associates that said: “I just bought 1,000 wheels from Senator Barnum from Connecticut, because he does pretty much what I want.”

Thompson: What was it about the character of government or the rules and customs of the time that you think made the late 19th century so corrupt as far as government goes?

White: The United States was becoming a major industrial country and a continent-spanning country. At the same time, it was incredibly averse to taxes and would not fund its necessary infrastructure and services. So it came to what scholars have called “fee-based governance.” In the 19th century, to get something done, you’d subsidize a corporation to do it, and that’s one source of corruption. The other thing is you take things like collecting the tariffs: Somebody has got to collect it, and that’s why the customs house becomes one of the plum appointments you can get. The head of the customs house in New York City makes more than the president of the United States because he gets to keep a certain amount of the customs he collects. You make sheriffs and deputy marshals tax collectors, and they keep a certain proportion of the taxes. That means that there’s going to be corruption from the post office all the way up to the sheriffs, to the customs houses, to people who are appointed offices. Everywhere in this system is going to get a fee, a bounty, and opportunity, which allows private profit to perform a public service. The result is corruption that is rampant throughout the whole system.

Thompson: One paradox of this era is that it was an astonishing time for material progress and also a decrepit time for human welfare. You write that men and women in this era suffered “the decline of virtually every measure of physical well-being.”

White: By 1880, in the middle of the Gilded Age, if you lived to be 10 years old, you would die at 48, if you’re an American white male, and you would be 5 feet 5 inches tall. You would lead a briefer life and be shorter than your Revolutionary ancestor. And you were one of the lucky ones, because on average, 20 percent of infants would die before age 5. You’re living in an environment where, as America urbanizes, there’s no reliable sewage system. There’s no pure water. There’s no public health.

Thompson: What did the Gilded Age build that’s most worth remembering?

White: It began to build public infrastructure—which allowed Americans to live better and to be in better health—and transportation infrastructure. The United States, unlike Europe, is this single country without tariff barriers between states, which can use the resources of the entire country. Did we do it efficiently? No. But we did it. And in the end, it became the basic source for much of the growth that followed.

The other thing we started to do, at Edison’s lab and at the Gilded Age universities, is build a way to create useful knowledge. We’d always been a nation of tinkerers and inventors, but then we began to systematize it for the public good. The final thing, and it’s not so popular anymore, is we begin to create a set of experts and expert organizations, which begin to take that kind of knowledge and to put it to public use.

Thompson: How did the excesses of the Gilded Age set the stage for the next era of American history and government, which was the Progressive era?

White: I think that the best way to understand the Progressive era is that the Progressives saw society as a machine. You don’t let a machine evolve. You design a machine. When a machine breaks down, you repair the machine. When you can get a better machine, you build a better machine. So Progressives begin to think civil society is something which is going to have to be managed all the time.

The great advantage of Progressivism is what it did in terms of distribution and equity. But the major drawback of Progressivism, which we struggle with still today, is that in essence, it becomes undemocratic. There’s tension in a democracy between rule of experts and having a country which ostensibly is under the control of people through their votes and setting the goals. That tension appears in the Progressive era, and it has never, ever gone away.