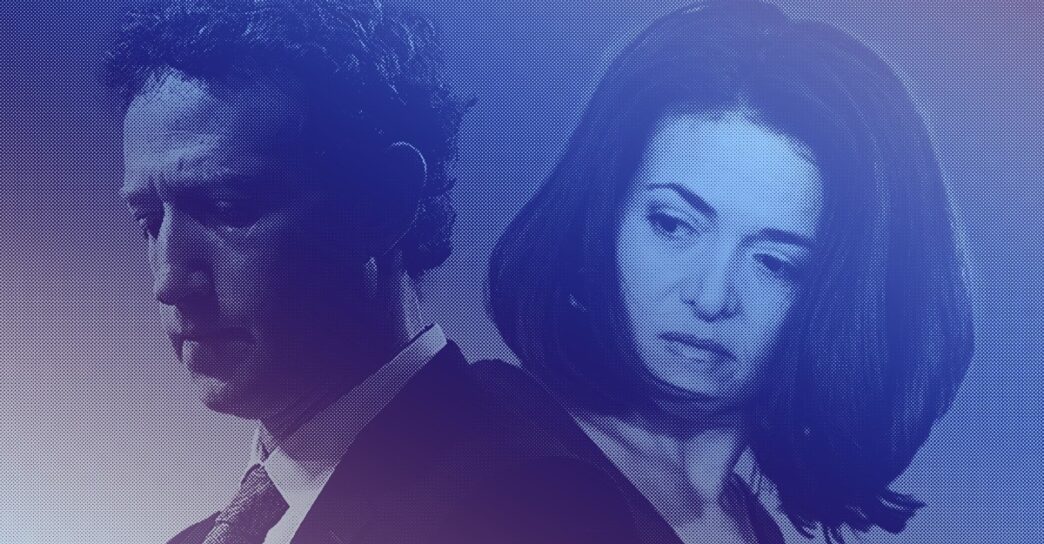

Perhaps the biggest surprise of Careless People, the new tell-all memoir by the former Facebook executive Sarah Wynn-Williams, is that a book chronicling the social network’s missteps and moral bankruptcy can still make news in 2025.

The tech giant—now named Meta—seems determined to make this happen itself. The company filed an emergency motion in court to halt the book’s continued publication, and in numerous statements, Meta’s communications team has derided it as the work of a disgruntled ex-employee. All of this has only generated interest: On Thursday, the book debuted at the top of the New York Times best-seller list for nonfiction and, as of this writing, was the third best-selling book on Amazon.

A general theme of the pushback is that Wynn-Williams, who worked on global policy at Facebook, is guilty of the same sins she documents in the book. “Not only does she fail to take any responsibility for her role in all of this,” Katie Harbath, a former director of public policy at Facebook wrote on her Substack, “but she is also careless in her account. She also gives no recommendations on how to do things better other than to say they should be done differently.” Andy Stone, a spokesperson for Meta, called the book “a mix of old claims and false accusations about our executives.” He has also shared posts from current and former employees that cast Wynn-Williams as an unreliable narrator. In one post, a former colleague expresses frustration that the book seems to take credit for his efforts at the company.

Given Wynn-Williams’s privileged position as Facebook’s first executive focused specifically on global policy, her perspective might differ from that of employees on other teams. Meta is a huge organization, after all. But the debates over the more gossipy anecdotes obscure the larger trends that surface through the book. I’ve never spoken with Wynn-Williams for a story or otherwise—she is currently under a gag order after Meta pursued legal action against her, claiming that the book violates her nondisclosure agreement—but her descriptions of Facebook taking actions in foreign countries without regard for consequences are similar to anecdotes told to me over the years by current and former employees. These stories are even more relevant in 2025, when tech’s most powerful figures have assumed an outsize role in American politics. All of us are living in a world that’s been warped by the architecture and algorithms of Silicon Valley’s products, but also by the egos of the people who have made fortunes building them.

I tore through Careless People despite being intimately familiar with many of the broad storylines—Facebook’s push into politics and the fallout from the 2016 election, its global efforts to expand in China, the platform’s bungled expansion in Myanmar that contributed to a genocide in the region. Wynn-Williams’s perspective provides crucial dimensionality to a well-trodden story, given her proximity to the company’s leadership.

But although it explores serious subject matter, the book is also not nearly as strident or sanctimonious as some other whistleblower memoirs. Wynn-Williams is comfortable reaching for an absurdist register: She recounts, for example, a scheduling nightmare that brought her to the brink of tears while trying to get Mark Zuckerberg a last-minute spot at the Global Citizen Festival in 2015: In her attempts, Wynn-Williams manages to anger an actor dressed as Big Bird and create logistical “issues for Malala and Beyoncé.” The spectacle culminates with a sweaty Zuckerberg onstage, “looking around desperately, like an animal in a trap.” The book is filled with similar anecdotes that capture the peculiar indignities of those catering to the whims of the most powerful people in the world. (When reached for comment, Dave Arnold, a spokesperson for Meta, referred to past statements the company has made about the book and cast doubt on Wynn-Williams’s status as a whistleblower: “Whistleblower status protects communications to the government, not disgruntled activists trying to sell books.”)

Early in Careless People, Wynn-Williams says Facebook asked her if “Mark should take credit for the Arab Spring.” In passages about Facebook’s expansion in Myanmar, she cites the executive team’s incuriosity about the country’s culture and politics. Later, when viral fake news stories on Facebook lead to riots and killings in Myanmar, Wynn-Williams details that the company had just one moderator who spoke Burmese, never posted its community standards in Burmese, and did not translate core navigation features of the platform into Burmese, including the button you use to report hateful content. News coverage in the aftermath of the genocide supported many of Wynn-Williams’s claims.

Wynn-Williams offers a few explanations for these problems over the course of Careless People. She suggests that executives like Zuckerberg simply don’t care about Facebook users once they’re on the platform. But there is also the company’s relentless pursuit of growth. Facebook’s obsession with gaining access to Myanmar and other Southeast Asian countries came around the same time that Facebook’s growth and stock were flagging post-IPO. Internally, stagnant user growth was referred to as “running out of road.” She describes Facebook’s growth team as willing to do almost anything to extend that road.

Nearly every insight and example provided in Careless People—the allegations that former Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg and the Irish prime minister secretly schemed on ways to dodge corporate taxes, the documentation of Facebook’s attempts to work with China to collect data on its citizens—traces back in one form or another to a blind obsession with scaling the business. All of it, of course, is meant to achieve Zuckerberg’s vague yet relentless mission to connect the world. When asked about these allegations, Arnold, the Meta spokesperson, told me, “We do not operate our services in China today. It is no secret we were once interested in doing so as part of Facebook’s effort to connect the world.”

Wynn-Williams’s assessment of Facebook’s mission aligns with what I know. In 2018, while reporting for BuzzFeed News, my colleagues and I obtained a memo written by Andrew Bosworth, one of Zuckerberg’s most loyal executives, outlining his personal strategy of growth at any cost. In the memo, Bosworth suggests that people could get hurt or killed as a result of Facebook’s expansions. Still, he is unequivocal: “The ugly truth is that we believe in connecting people so deeply that anything that allows us to connect more people more often is *de facto* good.” This same tone of self-assuredness, short-sightedness, and binary thinking are present in most of the conversations with Facebook executives that Wynn-Williams writes about (on Threads, Bosworth called Careless People “full of lies. Literally stories that did not happen”). It’s captured memorably early on in the book, when Wynn-Williams details the company’s young policy team’s struggle to come up with a mission statement of its own:

[For] Mark and Sheryl, it’s obvious. We run a website that connects people. That’s what we believe in. We want more. We want it to be profitable and to grow. What else is there to say? There is no grand ideology here. No theory about what Facebook should be in the world. The company is just responding to stuff as it happens. We’re managers, not world-builders. Marne just wants to get through her inbox, not create a new global constitution.

Reading Careless People, I became fixated on a question: What is left to say about Facebook? The company has been through more than a decade of mega-scandals, congressional hearings, apologies, and Zuckerbergian heel turns. Many people have experienced the ways that the platform has algorithmically warped and influenced our culture, politics, and personal relationships. It is difficult to say something new about the company that has, in large part, succeeded in connecting the world. A book revealing, in 2025, that Facebook has behaved recklessly or in morally reprehensible ways feels akin to arguing at length that oil companies are substantially responsible for climate change—almost too obvious to be very interesting.

And yet, something about Careless People—beyond the court order, the messy PR spectacle, and Wynn-Williams’s formidable storytelling abilities—feels urgent, even necessary right now. It’s not just that Zuckerberg is in the news for cozying up to Donald Trump, though that’s part of it. Paging through the book makes clear that even recent history rhymes with the present. Careless People is a memoir, but even Wynn-Williams’s most personal anecdotes speak to the power and authority that tech executives, their platforms, and their massive fortunes wield over so many.

American politics, in the second Trump administration especially, is as much a tech story as it is a political one. Elon Musk’s dismantling of the federal government via DOGE is a product of the same Silicon Valley ideology that Zuckerberg coined with his infamous “move fast and break things” motto. Similarly, Musk’s self-described obsession with rooting out waste, fraud, and abuse to make the government efficient shares a platitudinal vagueness with Zuckerberg’s long-standing mission to connect the world. Both ideas sound good on paper but are ultimately poorly defined (and executed even worse), leaving the same question unanswered: connection for what? Efficiency at what cost?

Careless People illustrates how this ideological vacuum is filled by its leaders’ fleeting whims and governed by their fragile egos. Zuckerberg, whose “disregard for politics is a point of pride” at the beginning of the book, is ultimately enamored by the power it brings. Slowly, Wynn-Williams notes, he becomes more involved in global affairs, eventually asking to make complex content-moderation decisions on his own. “In reality it’s just Mark,” she writes. “Facebook is an autocracy of one.”

The chaos of the past two months—the looming constitutional crises, the firings and rehirings—is what it feels like when a government is run, at least in spirit, like a technology company. Wynn-Williams’s book isn’t prescient; much of it is, as Meta notes, older news. What’s most disorienting about Careless People is that it is packaged as a history of sorts, but its real utility to the reader is as a window into our current moment, a field guide to tech autocracy.

In her epilogue, Wynn-Williams notes of the Facebook executives that “the more power they grasp, the less responsible they become.” Does that sound familiar? For now, the careless people have won. They’re in charge. The chaos Wynn-Williams has documented—we’re just living through a different version of it.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.