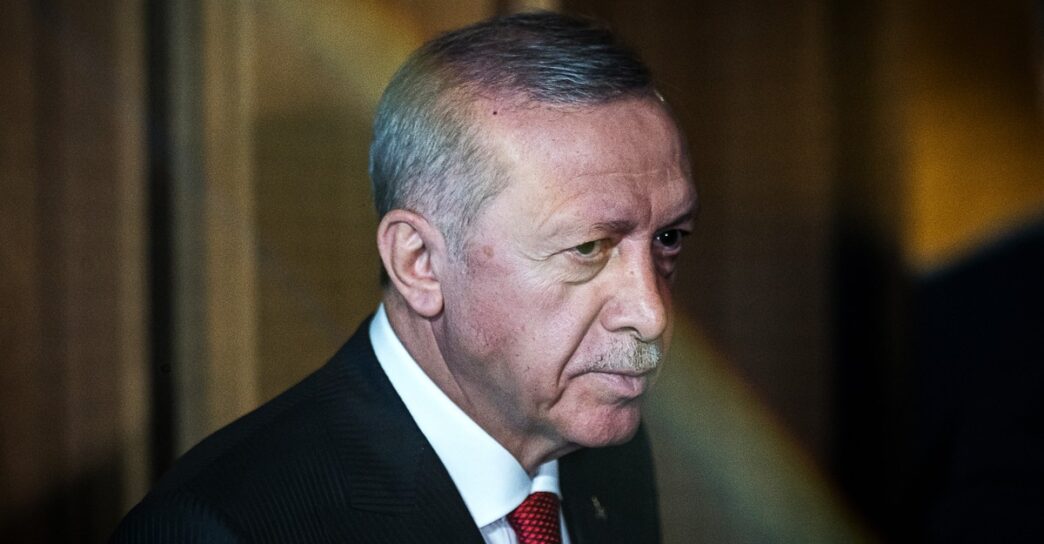

The Turkish Republic is on the brink. As Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, its would-be sultan, dismantles the country’s secular democracy, President Donald Trump has seemingly taken little notice. Soon, though, Trump will have no choice but to pay attention. While Erdoğan consolidates power at home and prepares to project it abroad, he has set the stage for a clash with Israel. Indeed, Turkey has quickly emerged as perhaps the greatest danger to the Jewish state in the Middle East, escalating the threat of a conflict he won’t be able to avoid.

Erdoğan and his Justice and Development Party have cowed their liberal opponents, co-opted most of the Turkish press, purged and restaffed the Turkish military—with special zeal after crushing a 2016 coup attempt—and revamped Turkey’s intelligence service. Last month, he arrested and falsely charged as a terrorist the most potent political rival he has faced since becoming prime minister in 2003: the mayor of Istanbul, Ekrem İmamoğlu. Erdoğan even revoked İmamoğlu’s university degree, making him, in theory, ineligible to run for president. The country has erupted in protest; in response, the regime has tightened its grip and arrested hundreds of demonstrators.

Erdoğan seems poised to use his growing power in service of imperialist aims. He has fused Turkish nationalism and Islamism with a renewed reverence for the Ottoman Empire, reversing the course that Kemal Atatürk, the republic’s founder, once set. Atatürk forged the modern Turkish state from the rump of the Ottoman Empire in part by focusing Turkish identity on nation rather than on faith. What drives Erdoğan is a kind of neo-Ottoman dream, starring himself in the role of sultan cum caliph, or, as he once put it, “a servant of the Sharia.” Despite domestic opposition to his rule, Erdoğan has a plausible path to that ambition. The truth is that many Turks, even secular ones, have a certain affection for their country’s imperial past, when Turks were feared invaders rather than migrants searching for industrial jobs.

Erdoğan’s grand designs appear to include establishing himself as the Muslim world’s principal champion of anti-Zionism. The president has routinely hosted Hamas leaders for official visits and has referred to the architects of the October 7 attack as a “liberation group.” Late last month, in Turkey’s largest mosque, he reportedly told a crowd of worshippers: “May Allah, for the sake of his name, Al-Qahhar”—the Vanquisher—“destroy and devastate Israel.”

In turning against Israel and in favor of Hamas, Erdoğan is riding a wave of anti-Zionism and anti-Semitism that has been rising in Turkey since at least the 1980s, especially on the secular left. But Erdoğan’s realignment amounts to an extraordinary reversal of the country’s earlier history. After World War II, Turkey was the most pro-Western Muslim-majority country in the world. It recognized Israel in 1949—the first Muslim nation to do so—and has been a NATO member since 1952. Turkey’s alliance with the West, however, has long been turbulent. Over the past 20 years, the European Union has made clear that Turkey is not welcome to join. Nor have the U.S. and Europe really sided with Ankara against the Kurdish groups it believes threaten its territorial integrity in the southeast. Erdoğan has, for his part, characterized the West as a purveyor of values that traditional Muslims find decadent and sinful.

The Turkish president has intensified a long-held desire in his country to gain greater distance from the United States and NATO, so that Turkey will be free to profit from its strategic position and squeeze the world’s power players—including those outside the West—for all Ankara can get. The big exception, however, has been Israel, where Erdoğan’s Islamist sympathies and ambitions have curtailed commerce and tourism, and inflamed opposition.

Now that Erdoğan has spurned the West and set his sights on Israel, Turkey could prove more worrisome for Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu than virtually any other country. Its armed forces are large, well equipped, relatively well trained, and backed by a GDP of more than $1 trillion. A recent Israeli security assessment, the Nagel Commission report, identified Turkey as a growing threat, given its military presence in neighboring Syria and its imperialist ambitions in the region. Those factors, the report warned, could “exacerbate the danger of a direct Turkish-Israeli conflict.”

Trump is apparently eager to smother tensions between the two countries before they ignite. In a press conference with Prime Minster Benjamin Netanyahu last week, Trump presented himself as a potential mediator: “Bibi, if you have a problem with Turkey,” he said, “I really think I’m going to be able to work it out.”

He could be right. The Pentagon and Langley still have extensive dealings with Ankara, providing leverage that Washington could use to restrain Erdoğan. When the Turkish leader asked Trump during his first term to withdraw American forces from Syria, he agreed. (After all, Trump considered Erdoğan a “friend.”) Then–Secretary of Defense James Mattis and others walked Trump back, but now the president has no such counselors around him to deter a deal with Erdoğan, whom he lauded at the press conference.

One carrot Trump could use is readmitting Turkey to America’s F-35 program. Trump stopped selling the prized fighter jets to Ankara in his first term, after Erdoğan purchased Russian anti-aircraft batteries. But a call last month between the two leaders has reportedly made Trump consider the possibility of restarting sales as well as lifting sanctions.

To discern Erdoğan’s next steps, look to Syria, where he could begin to mobilize against Israel. Erdoğan has ample leverage there because of his support—via cash, arms, and intelligence—for the Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) militia, which toppled the Assad regime in December. Syria figures to remain fractured, poor, and violent, especially in the Kurdish areas near the Turkish border. Erdoğan likely wants order to be restored, partly so that Syrian refugees in Turkey go home, and partly because a power vacuum in Syria benefits the Kurds, who control most of Syria’s oil—with U.S. military protection (unless Trump removes it).

The Israelis are concerned that, with Turkish proctoring and aid, HTS could eventually become a formidable military force capable of replicating the cross-border threat Hezbollah posed from Lebanon. (Although an HTS leader has pledged not to strike Israel, other members have historically endorsed attacks on the country.) Even worse for Israel is the scenario that Ankara establishes an air and naval presence in bases across Syria.

For now, though, the likeliest course of action for the Turkish president is to find small-scale ways to support attacks on Israel, especially those by Palestinians. Israelis have reason to be concerned about this possibility: In July 2023, they intercepted a shipment from Turkey to Gaza of ammonium chloride, a chemical that Hamas has used for rocket propellant.

If Trump wants to reduce the risk of yet another regional war, he will need to find ways to cultivate greater influence in Ankara. Simply calling Erdoğan a friend won’t cut it.